125th Anniversary Reflection - Part 3

Reflection

The Oblates of Mary Immaculate are celebrating 125 years of serving the Church in Australia. It is an opportunity to give thanks for the past, to acknowledge the many blessings in our Province today and to prepare for another 125 years of service in Australia. The De Mazenod Family Gathering is an opportunity to build and strengthen connections between the Oblate ministries and explore structures for a Lay Association. Please keep the De Mazenod Family Gathering (14-18th August) in your prayers and continue praying for Vocations to the Priesthood and Religious life.

The following reflection is part of this journey, a series of reflections on our history written by Fr Austin Cooper OMI.

Continuing Fremantle and the Oblates:

The original agreement with the Bishop involved undertaking an ‘Industrial School’ for delinquent boys, a ministry in which Oblates were involved in Ireland. The demands of Fremantle and personnel restraints left the Oblates less than enthusiastic about this aspect of the plan, but Bishop Gibney was insistent. He reminded the Oblates that ‘I offered 300 acres at Subiaco for this purpose with leave to collect throughout the Diocese to defray expenses . . . . The Government will give an allowance of one shilling per diem for children admitted by their officers.’

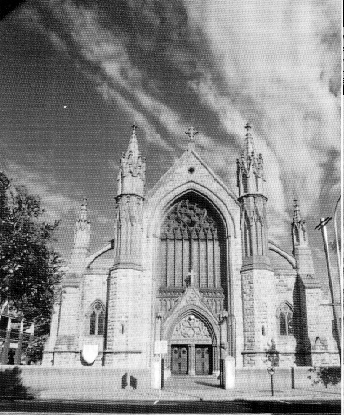

The ensuing tension was to throw the Oblate presence in Fremantle into jeopardy. The Council of the British Province was not sure that the proposed industrial school was a binding part of the agreement. While from Fremantle, Fr. Roger Hennessy reported that ‘our position here is anything but agreeable. The subscriptions to our new Church have come to a standstill. The people are displeased by the report of our leaving, and we, on our part, have no encouragement to continue. . . I sincerely hope that we shall not have to abandon Fremantle.’ Obviously, the Oblates had understandable concerns about the availability of personnel and the Bishop had a strong point in his reading of the original agreement. But in the dust of debate clarity of vision was impaired.

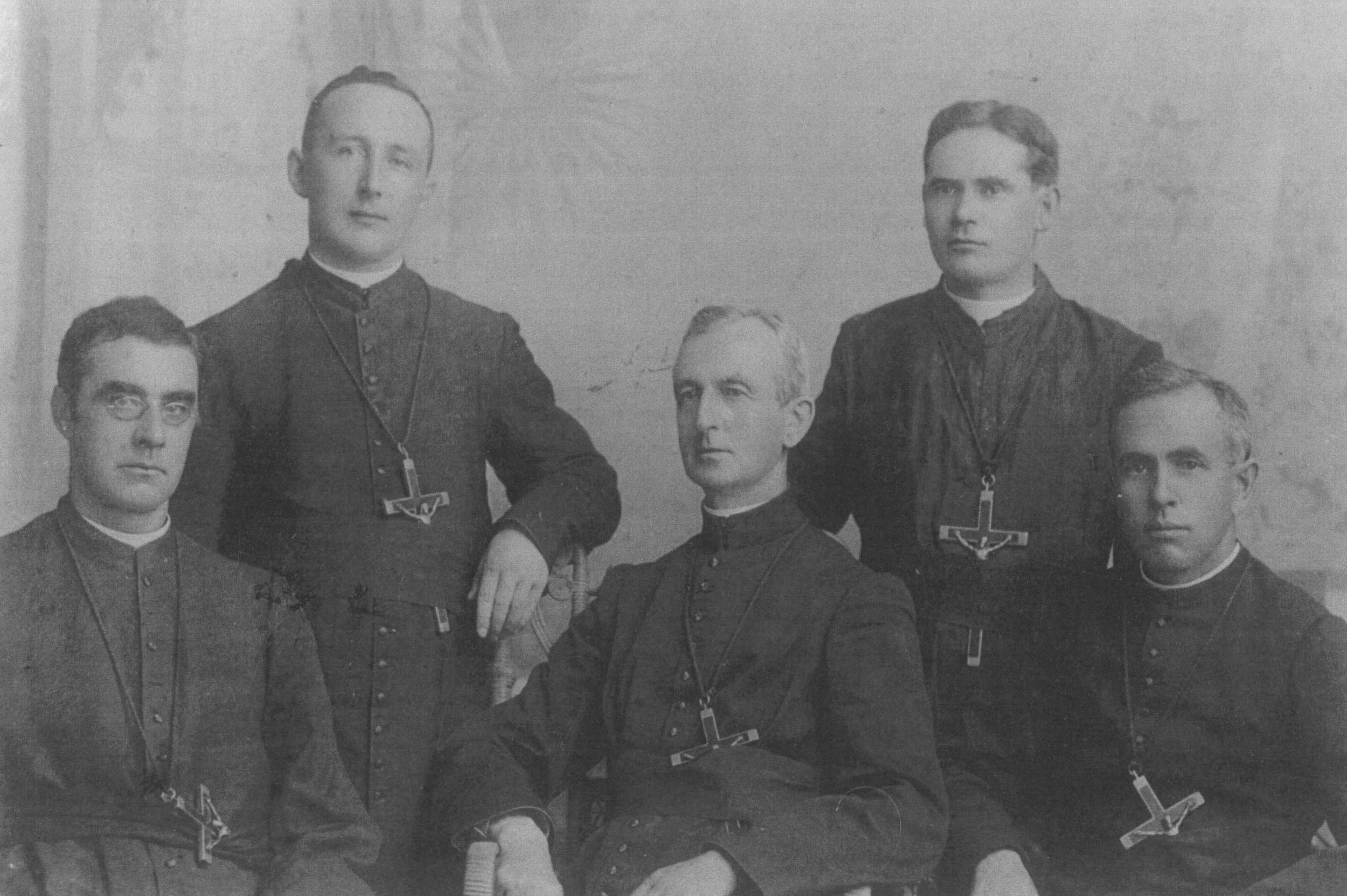

Fortunately help was at hand. Two Irish Oblates, Frs Stephen Nicoll and Patrick Brady were visiting WA to preach Missions and were asked to make a submission to the Oblate General Council then resident in Paris. Fr. Nicoll made a very balanced submission: the choice was between abandoning the mission and returning home or maintaining an Oblate presence in the Australian Church which necessitated accepting the industrial school. He was very much in favour of the latter as he saw the Oblate presence as ‘full of hope for the future.’ His wisdom saved the day. The contract was signed in 26th December 1896 and the foundation stone laid on the following March 17th, Fr. Daniel O’Ryan from Fremantle was appointed Superior and he was joined by three Oblate Brothers experienced in this ministry in Ireland: George Nolan (aged 26), Daniel Howard (aged 38) and Michael Boland (aged 39). Conditions were tough. Added to this was a paucity of numbers: in 1911 there were only 10 boys committed by government agencies and another 21 sent by parents (and for these there was no government subsidy). By the time the venture closed in 1921 some 219 boys had been sent from courts and 22 as private boarders.

One encouraging by-product of the establishment of Glendalough was the decision to give a measure of ‘self-government’ to the Oblate mission: the Oblate Vicariate of WA was established with two houses: six priests at Fremantle and one priest and five brothers at Glendalough. This appeared an encouraging sign, yet with the small population in WA there was little hope for future local recruitment. The Oblate presence was still (and long remained) very dependent on personnel from afar.